After more than 80 years of history the American and European Drug Agencies (FDA and EMEA) approved the first pulmonary delivered version of insulin (Exubera®) from Pfizer/Nektar early 2006. However, there is concern about the long-term effects of inhaling a growth protein into the lungs. It was assumed that the large surface area consequence the likelihood of hypoglycemia. Other problems were the inability to deliver precise insulin doses, because the smallest blister pack available contained the equivalent of 3 U of regular insulin and this dose would make it difficult for many people using insulin to achieve accurate control, which is the real goal of any insulin therapy. For example, someone on 60 U of insulin per day would lower the blood glucose about 90 mg/dl (5 mmol) per 3 U pack, while someone on 30 U a day would drop 180 mg/dl (10 mmol) per pack.

Precise control was not possible, especially compared with an insulin pump that can deliver one twentieth of a unit with precision. Another disadvantage was the size of the device. The Exubera® inhaler, when closed, was about the size of a 200 ml water glass. It opened to about twice the size for delivery. To our information also other companies (Eli Lilly in cooperation with ALKERMES, NovoNordisk (AERx®, Liquid),Andaris (Powder)) stopped further development and it is unclear whether an inhaled form of insulin will ever be marketed, because of the problems that have occurred. Only Mannkind (Technosphere®, Powder) is still working on a Phase III trial. However, our review will briefly summarize the experience regarding inhalant administration of insulin and will describe potential future developments for this type of therapy focussing on the lung.

However, because of their large molecular weight, hydrophilia, instability against chemicals and proteases, and poor intestinal absorption rates these macromolecules cannot be administered orally and must be given parenterally. Unfortunately, techniques for parenteral drug application (e.g., subcutaneous, intravenous, or intramuscular injection) are invasive and require the compliance, especially inpatients with chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus). In consequence, a number of methods for controlled injection or alternative routes of drug administration have been developed (1, 2). Inhalation is an important tool for non-invasive administration of low molecular weight pharmaceuticals and macromolecules for systemic treatment.

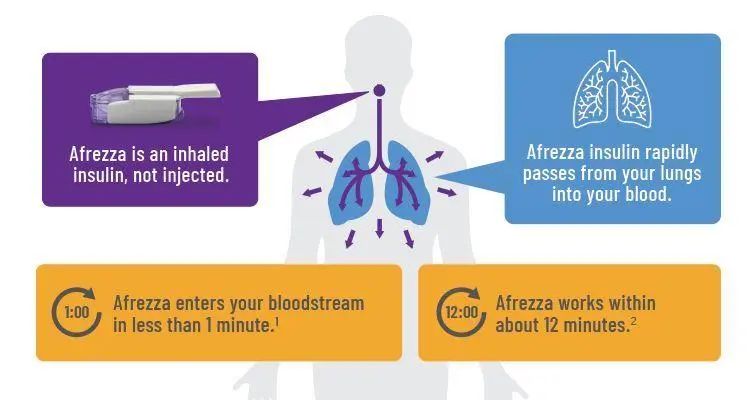

This way of drug administration has the benefit of a large alveolar absorption area of 70 m2 - 140 m2 which is about the half of a tennis court (compared with 180 cm2 in the nose cavity), a good perfusion of the absorptive area (about 5 l/min), a very low thickness of the alveolar epithelium (only between 0.1 and 0.2 µm) and a short total distance between epithelial surface and blood in the alveolar area (between 0.5 and 1.0 µm compared with 30-40 µm distance between mucus surface and blood in the bronchial system), a low presence of local proteases and peptidases, a marginal variance in the amount of mucus production, a rapid dissolution of the administered insulin in the alveolar mucus layer after its deposition, and the absence of a hepatic first-pass effect (1-6).

An optimal pulmonary deposition is achieved with a slow and deep inhalation procedure. In addition, variations in lung morphology and ventilation due to diseases (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)) and individual factors (e.g., smoking) have an influence on the alveolar deposition of inhaled particles. Finally, the absorption of the biomolecules after alveolar deposition is affected by structure and function of the physiological pulmonary defence mechanisms (e.g., proteases/peptidases, alveolar macrophages, physiological absorbance barriers) and specific properties of the biopharmaceuticals (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity, solubility in water and lipids).

The application of biomolecules by means of different inhalation approaches has been investigated in a large number of studies (4, 7, 8, 12, 13). In principle, some of the biomolecules can be given without additives. Other large molecules, especially peptides and proteins, require stabilisers and inhibitors of phagocytosis (e.g., protease inhibitors, microspheres, liposomes) or absorption enhancers (e.g., detergents, bile acids, cyclodextrins) which can cause tissue irritation (1, 2, 4, 8, 11, 14-16). Compared with absorption enhancers, the use of carrier-based systems (e.g., liposomes and microspheres) has some more specific advantages for sustained and targeted drug delivery as compiled in Table 1 (17).

However, most experience is available for the inhalation of insulin. In addition, from the large number of substances insulin is the one with the greatest relevance because of the large number of diabetic patients worldwide. In our review we describe the current status and problems of devices for pulmonary administration of insulin.

italiano

italiano  English

English français

français русский

русский español

español português

português العربية

العربية 日本語

日本語 한국의

한국의 magyar

magyar